Out of the Shadow: 7 Types of Shadow Character Archetype That Make Great Protagonists

Archetypes don’t hem you in, making your story flat or feel like regurgitated slop. Archetypes are the tools all good writers learn in their infancy, master, and then ‘forget’. There’s absolutely nothing shady about using an archetype.

Speaking of shade, let’s talk today’s archetype, the Shadow.

What is the Shadow Archetype?

Well, why would I think for myself when I can just quote the father of this series, Christopher Vogler:

“the Shadow represents the energy of the dark side, the unexpressed, unrealized, or rejected aspects of something.”

The reason the Shadow is called the Shadow is because, well, that’s what it is. If we are the Hero, then our Shadow is the dark force that follows us around when we stand in the light. The stronger the light, the stronger the shadow.

What makes the Shadow special is the light that casts it. Every Shadow is specific to the light that casts it. Hannibal Lecter only works as the Shadow to Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs because he perfectly exemplifies the darkest parts of her.

Well-designed Shadows aren’t just external forces for the Hero to rise up against, they’re thematic. If your Hero represents openness, freedom, and free-thought, then the Shadow would be a procedural, controlling, dominating AI, for example. More than any other relationship in your story, the relationship between the Hero and their Shadow is crucial to the success of your story.

There can of course be multiple Shadow’s, but this doesn’t seem the appropriate place to open that particular can of worms. Instead, we’ll focus on characters that represent the thematic ‘death’ of your story.

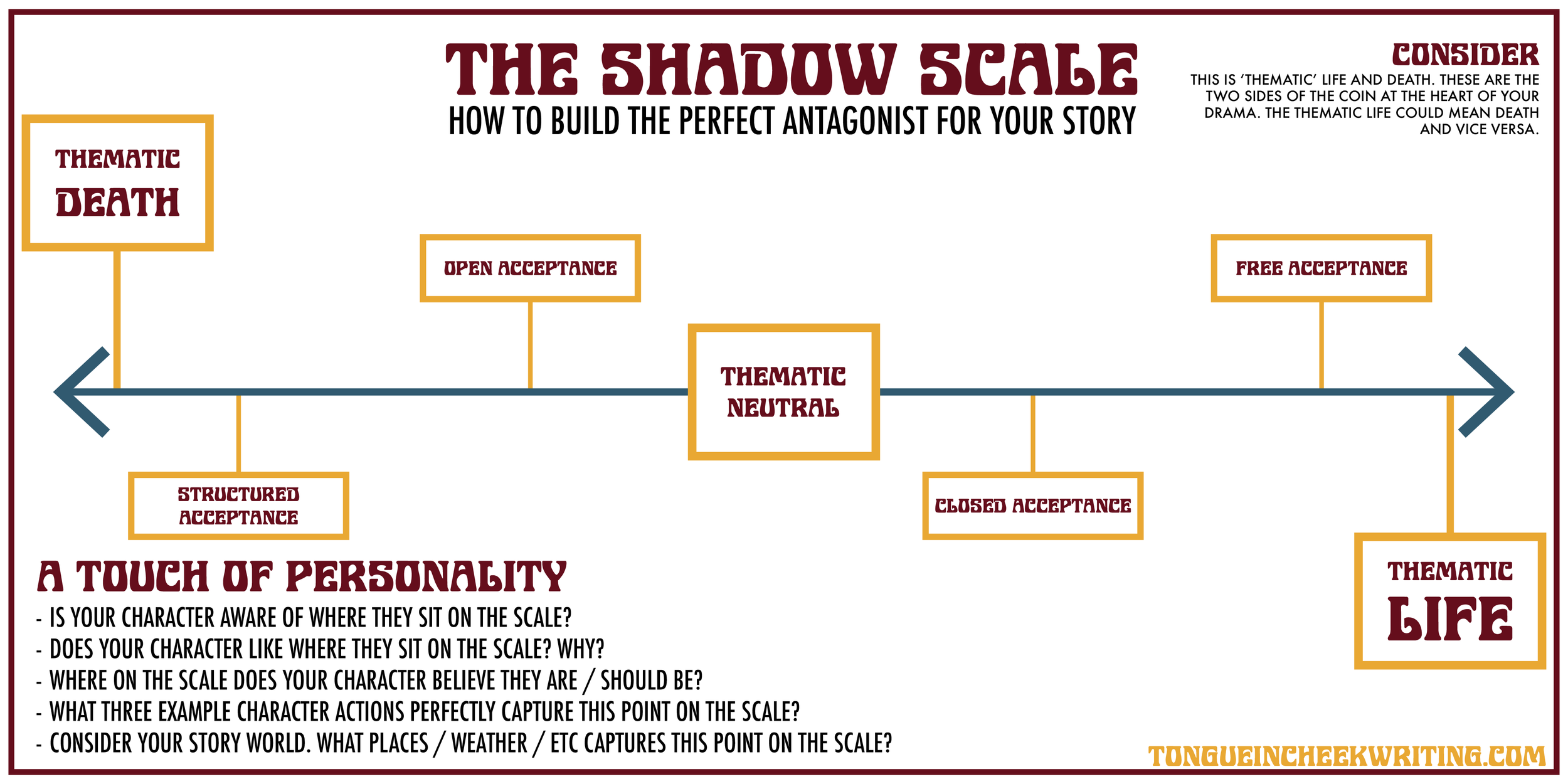

It’s important to note that they represent thematic death, not actual death. Sometimes, depending what a messed up writer you are, death can actually represent ‘life’ and life would be the thematic ‘death’. It’s a scale:

How to turn the Antagonist into Protagonist

As with all the archetypes in this series, the Shadow is a function, not a character. Unlike all other archetypes, though, the Shadow is intrinsically linked to character. Magneto is the perfect Shadow of the X-Men franchise because, although he shares a goal with the X-Men, his methods and ideologies drive him into direct conflict with his best friend. It’s that simple truth that allows the relationship of Charles Xavier and Magneto to be so complex.

The same should hopefully be true of the Shadow of your own work. In The Writer’s Journey, Vogler states that “a strong enemy forces the hero to rise to the challenge.” In other words, as one force rises, another rises to meet it. From the perspective of your source text, that’s pretty cut and dry:

- Hero do good

- Villain do lots of bad

- Hero must get more good to overcome lots of bad

But telling the story from the perspective of your Shadow lets you create some truly murky waters, potentially developing your theme into something truly mature.

- From the X-Men’s perspective, Magneto is a fallen Ally whose pursuit of Mutant rights has become fuelled by rage and violence. When Magneto attacks humans in pursuit of his goal, the X-Men are forced to rise up and save lives.

- From Magneto’s perspective, the X-Men are ineffective bystanders that are complicit in the genocide of their own people. When the X-Men rush to support the instigators of that genocide, Magneto is forced to rise up and save Mutant lives.

The events are the same, but what they mean vary dramatically depending what side of the battlefield you’re on.

Call me a madman, but I think audiences in 2025 need to be shown this more than any other.

If nothing else, the Shadow archetype is the narrative solution to the culture wars, but only if you fully invest in how they see the world. It’ll take you to some dark places, and make your skin crawl. But then, it’ll also do that to your audience, and it’s about time the echo chamber walls were broken down.

But, enough politics, I promised you seven types of Shadow, and here they are:

Types of Shadow

The Helpful Shadow

Definition

How can a Shadow be a complete inversion of the Hero and be helpful? Well, sometimes the Hero needs to embrace a bit of the dark side in order to further the plot. Helpful Shadows are a mixture of Mentor and Shadow. They will guide the Hero through the story, using their knowledge to coax the Hero out of the light and into the void.

Very often Helpful Shadows will perceive themselves as Allies to the Hero. Whether they’re aware of their shadowy nature or not, their primary goal is to help the Hero.

How to Adapt

How did Hannibal Lecter end up in that glass cell?

What happened to him after he escaped?

Both of those questions have been answered to varying degrees of success, and they’re the kinds of questions you should be asking about your Helpful Mentor.

Redeemed Shadow

Definition

Some Shadows know where they are when a story starts. They wear the ‘mask’ of Shadow, doing all the dark grizzly Shadow things, but by the stories end they’ve been brought back into the thematic light.

It’s a tale as old as time, a tune as old as song…

I’m not entirely sure why, but many Redeemed Shadows have something of an animalistic slant to them. The Beast from Beauty and the Beast, the Hound from Game of Thrones, they all seem to go on a beastly-to-heroic journey.

How to Adapt

The Beast wasn’t born a beast. The Hound wasn’t born a hound. Redeemed Shadows are uniquely tragic. We’ve seen how their story ends, but let’s see how it started.

Vulnerable Shadow

Definition

While Redeemed Shadows are designed to elicit empathy, Vulnerable Shadows are designed to make you think. Then feel. Then think about what you’re feeling.

Sometimes Shadow’s aren’t solid darkness, but more like the flickering shadow cast by a dying candle. You’re never quite sure where the light is, or the dark. They teeter between light and shadow, presenting a morally complex version of the Shadow.

Even though we know they’re the Shadow, part of us believes they’re right. Why? Because they’re vulnerable. They don’t need a tragic backstory to be vulnerable, they just need to be real.

Sure, they’re the wicked witch, but they’re also lonely.

Sure, they’re a cocksure knight with incestuous tendencies, but they’re also fuelled by their duty.

How to Adapt

Vulnerable Shadows are hard to adapt for one simple reason: there’s never just one. Very often a Vulnerable Shadow will be one of a number of Vulnerable Shadows. Your story world Is a morally grey one, where characters teeter between light and dark at all times.

So, embrace that. Find a character that teeters more than any other, and focus on them. Why do they jump back and forth between light and dark? What is light and dark to them? Don’t ask “why” this is light and that is dark, to Vulnerable Shadows light and dark simply are what they are. It’s innate.

Use the character you pick to explore the culture of your story world. The rules, the politics, make this Vulnerable Shadow the epitome of that grey area and go wild.

And I’m not just talking story. Go wild on medium. Make this character start a podcast set in-world. Write their diary, do whatever it takes to get this character under your audiences skin.

Tragic Shadow

Definition

I said not to ask “why” a Vulnerable Shadow thinks the way they do. That’s because “why” is the question that separates the Vulnerable Shadow from the Tragic Shadow. While Vulnerable Shadows darkness is intrinsic to who they are, the Tragic Shadow finds themselves in the void with a tangible reason.

Something has happened, or is happening, to this thematically neutral character that forces them to exist in the shadow realm. Perhaps they discovered their superpowers while suffering an atrocious holocaust. Or maybe they were a pirate, doing what pirates do, when they plundered too deep and ended up cursed.

Tragic Shadows exist, always, in the thematic death area of a story. Their gift is moving the goalposts in the audiences mind. We know that Barbossa is doing evil things, but we get it, because it must be awful being starving, exhausted, and on the brink of death at all moments, never allowed to die. It would drive anyone mad.

We know that Magneto is a murderer and a zealot (more on them later), but he’s someone who has suffered persecution since his earliest memories. When Mutants are attacked, he is reliving his past trauma over and over again.

Tragic Shadows know they’re in the shadow realm, but life has put them there and given them the tools to shape that darkness to their advantage.

How to Adapt

Tragic Shadows, in many ways, are addicts. They know they’re in the thematic void, but they either don’t care or they can’t stop. A path of such thematic self-destruction makes for wonderful drama fodder.

Every Hero has a ‘ghost’, and the Tragic Shadow is completely governed by theirs. As their name suggests, they’re tragic characters. So at least if you do make this character into a protagonist, you’ve got the genre sorted!

Do you drive your character deeper into the abyss? Do you pull them from it? Do you invert the abyss and give the character exactly what they want? What if Magneto won? How would that shape the world?

The Zealot

Definition

Most Shadow’s fall under this bracket, but I felt it deserved its own place in the pantheon. The Zealot is the shadow made manifest. Who cares where they came from? Who cares why they want what they want? They’re something like the Trickster in that regard, they just are.

Zealots are so utterly convinced by their goal that nothing and nobody will ever change them. Okay, sure, Thanos had a brief moment of backstory in Avengers: Infinity War, but nobody shed a tear for the Titan. He wants what he wants because he believes in his soul that it’s right.

As a Shadow, their ‘want’ often aligns with the Hero, which allows you a certain liberty when writing them. If your Hero’s want is clear and compelling, audiences will forgive you if the Shadow is an unexplained echo of that. Moriarty, especially in the Sherlock series, shares Sherlock’s want to be the smartest man in the room. Thematically, they’re tied. We know why Sherlock is the way he is, and Moriarty is the perfect foil to bring that out, we don’t need to know why Moriarty is the way he is.

The Zealot is the other side of the coin because they are.

How to Adapt

How do you adapt this character? Carefully.

Them being an enigma is part of their charm, so be careful if peeling back the layers to make the Zealot a protagonist.

As much as I don’t like the visual style of the new The Lion King movies, they do something very clever in Mufasa with the character of Scar. Scar is a character that wants the throne because he wants it. That’s his purpose. He ‘wants’ because Simba doesn’t ‘want’. In Mufasa, rather than make Scar into a Tragic Shadow, they elevated his desire for the throne because he ‘deserves’ it.

Develop the Zealot. Yes, all zealots started somewhere, but some were destined on this path. It’s just who they are. Seeing that in different lights might not change how your audience sees the Zealot, but it will enhance it.

Internal Shadow

Definition

You won’t like this one when they’re angry.

“When the protagonist is crippled by doubts or guild, acts in self-destructive ways, express a death wish, gets carried away with his success, abuses his power, or becomes selfish rather than self-sacrificing, the Shadow has overtaken him.”

Time and again, in some of the best stories ever told, the Shadow was inside the Hero all along. This is where the psychological function of the Shadow and their narrative function overlap.

Internal Shadow characters are often split, sometimes literally, down the middle. You could say, they’re quite… two faced? No?

Fine.

Of all the Shadow’s, ironically the Internal Shadow is one of the least complex. One half of this character represents thematic life, and the other represents thematic death. The intrigue is in how they conflict.

Some great examples, other than Mr Harvey Dent, would be Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, or of course Bruce Banner and the Hulk. Even werewolves fit this particular type.

How to Adapt

What you’ll notice about some of the above examples is that they’re already protagonists. Less so Bruce Banner these days, but that’s a rights issue, not a story one. The reason is simple, they make the best protagonists. Two things’ writers struggle with are inner conflict, and outer conflict. These characters come pre-packaged with both.

The Fore-Shadow

Definition

“And this is what you could have won.”

Sometimes, protagonists know that jumping into the void would work. Just one time. Except it’s never just one time. Fore-Shadow characters once stood in that exact moment and jumped.

The Fore-Shadow is a reminder of the stakes, manifested in a character. They’re often not the main antagonist of a piece, but that doesn’t make them less important. Without Jacob Marley, Scrooge would never have changed his ways. Without Gollum, Frodo wouldn’t have fully grasped the stakes of staying true to himself.

How to Adapt

Fore-Shadow characters once stood in that exact moment and jumped. So, show the jump. Show the fall to the Dark Side…

Wait, I think I’ve got it.

Make a prequel trilogy!

In all seriousness, why not?

Go to that dark place. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. The Fore-Shadow can do something for your audience that almost no other character can:

They show that anyone, even you, can fall under certain pressures.

LEARN MORE

If you want to learn more about Transmedia storytelling and its applications, click HERE.

If you want to see some suggestions for Transmedia experiences, I make Cinematic New-Niverses which you can see HERE.

If you’re looking for comprehensive, concise, and constructive feedback on your script, check out my Fiverr profile to see how I can help, or contact me! It’s cheap as chips and may just get you that Oscar!